We may have a few lambs this season as we borrowed a Tup on the 14th of October, and so could lamb around the 13th of March. It is not worth scanning our small flock of Dorset Downs and so, as they are a naturally sturdy breed around 75 to 90 kilos it is not easy to see any early signs of pregnancy. They are in good condition, even so, we shall observe them closely to get the amount of extra nutrition right for them. Too much feed means big lambs but difficult lambing, whereas too little (especially with twins) may make it hard for the mother to produce enough milk to feed her offspring.

I have intended to cease lambing for some years, and we are now down to eight ewes. But we continue as somehow it seems ‘right’ to have a few animals around. They give us immense pleasure, (and heartache) and they taste good. In addition, sheep are a cheaper way turning grass into protein than any concrete and stainless-steel food factory. Also, food miles would be zero if politicians encouraged local small-scale abattoirs.

Thirteen thousand slaughterhouses operated in Britain the year I was born, but fifty years later it was one thousand. Even in 1990 most market towns including Ledbury still had their own, but unsurprisingly bureaucrats wanted full control, and through regulations, reduced the number to fewer than three hundred today.

Today most food is bought from supermarkets, and they know that sight dominates what we pick off the shelves. They make packaging colourful, and so plainly packed home-grown or locally produced food cannot achieve the colourful, regularity and standardised appearance of Aldi or Waitrose. On appearance and longevity, the supermarket wins easily but, that win is achieved by chemical treatments and additives. For some folk however, appearance is not everything. We can smell and taste, and feel texture. We know that home-grown and locally grown food excites these senses in ways homogenised processed food cannot. Local food also contains more natural nutrients, minerals and vitamins and its taste is fresher. I love our own lamb, with mint, potatoes, peas, beans, purple sprouting, carrots, and leeks lifted from the garden an hour earlier. ‘Mr Tesco, eat your heart out!’

However, most people are less fortunate: they do not have the space to grow their own veg or keep livestock or chickens. This thought brings me to a recurring theme of View from the Pew, Gratitude. I hear the word grateful at least once a day when I speak to local people, and this sense of gratitude is both personal and social. I think it is prompted because we ‘dwell’ in a beautiful landscape whilst also believing our common survival is inextricably linked with that of the landscape. We have an identity with the landscape which was moulded by the forces of nature long before the political forces of church and state drew boundaries of Parish for their administrative convenience. Boundaries which they adjust from time to time out of economic necessity and demographic change.

I once tried to explain this sense of rural community to a church official from the city, but it was clear that his notion of community excluded those who did not fulfil his criteria of acceptability. Such a narrow concept of community has always been integral in the world of hierarchy, but I cannot find it in the Gospels. The New Testament reveals a radical difference between the secular and religious thinking of the old world and the new. From AD 34 onwards: a core purpose of a religious organisation was to provide a place where we ordinary sinners may gather in hope of redemption through love. It was not to be a place where the righteous pen regulations and draw boundaries of exclusion.

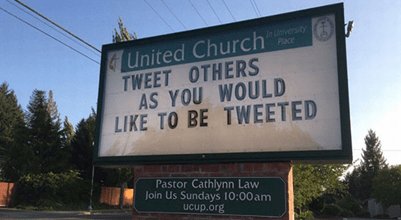

But talking of setting boundaries and the power of the written word reminds me of the sign outside a church in Tacoma Washington State. USA